Feature image by Lynn Gilbert.

Julia Bryan-Wilson is an art historian of enormous productivity, insight, range, and flair, with copious writing and curating credits, abundant laurels from diverse institutions, and generations of student acolytes. Her library to date includes Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era (University of California, 2009, named a best book of the year by the New York Times and Artforum); Art in the Making: Artists and Their Materials from the Studio to Crowdsourcing (with Glenn Adamson, Thames & Hudson, 2016); and Fray: Art and Textile Politics (University of Chicago, 2017, a New York Times best art book of the year and winner of the Frank Jewett Mather Award, the Robert Motherwell Book Award, and the Association for the Study of the Arts of the Present Book Prize). Great books all, but only representing a fraction of Bryan-Wilson’s contribution to culture.

To understand her voice in toto, one also has to check out her literally hundreds of journal essays, magazine reviews, museum catalogue pieces, anthologies, and artist’s books, or take one of her classes on modern and contemporary art (generally framed through a queer lens, and always running far afield of the traditional American canon). Decades of labor in the factories of academia and contemporary art have turned her into that rare kind of figure—at once ubiquitous and semi-shrouded, a scholar of sterling citizenship whose perfect bindings come as signal events.

All of which is to say, the arrival of her new monograph on the under-understood midcentury artist, Louise Nevelson (1899-1988), is a big deal. It’s no surprise, either, that the book casually demolishes many of the basic premises of the artist monograph. Divided into four smaller books, thus inviting the reader to approach from multiple angles, and incorporating many grassroots voices into the weave of argument, alongside those of august scholars and the occasional first-person musings of the author herself, the book is at once idiosyncratic, politically avant, and effortlessly, gracefully polyphonic.

It’s a major book by a major art historian that also reads as a missive from a ridiculously erudite friend—or at least it does to me, someone who’s known Julia since we were both about twenty years old, who put on art shows with her in the DIY wilds of Portland in the 90s, and who’s learned half of what I know about art from our never-ending and thoroughly joyous conversation.

*

Jon Raymond: Let’s start simple. How far back does your fascination with Nevelson go? Were there any pivotal moments that led you to write this book? Any signs or portents that guided you?

Julia Bryan-Wilson: I had never written a monographic book before—that is, a close study of a single artist—and I came to her as my subject gradually and hesitantly. I was apprehensive about how I would approach Nevelson’s impressively large and impressively repetitive oeuvre. But I kept returning to her art, especially her wood-based assemblages painted black. Why did this idiom emerge for her in the 1950s and why did she pursue it so insistently until her death?

Within art history, Nevelson’s sculpture is both pervasive and strangely neglected. Though I might have encountered Nevelson pieces in museums as a student, she was not included in the 20th century Western art surveys I took. Nor has there been a robust critical literature dedicated to her as there has been for, as a counter-example, Louise Bourgeois.

In trying to trace my own exposure to her art, I realized she was hiding in plain sight throughout my life—she was featured in Highlights for Children magazine when I was a kid, and she installed a prominent public sculpture in a busy intersection in Houston, TX where I grew up, etc. At the same time, I recall looking through the standard art history textbook as a teenager—H.W. Janson’s History of Art—and there were no women included at that time, literally not one.

I recall looking through the standard art history textbook as a teenager—H.W. Janson’s History of Art—and there were no women included at that time, literally not one.When the revised edition came out in 1986, Nevelson was one of a small handful of women mentioned. And she was one of the select few female artists who became visible—and in fact widely known—in her own lifetime. As a feminist interested in how the category of art is shaped by power and gender, I felt there was a larger story to tell about visibility and erasure via examining Nevelson’s peculiar (influential yet diffuse) presence.

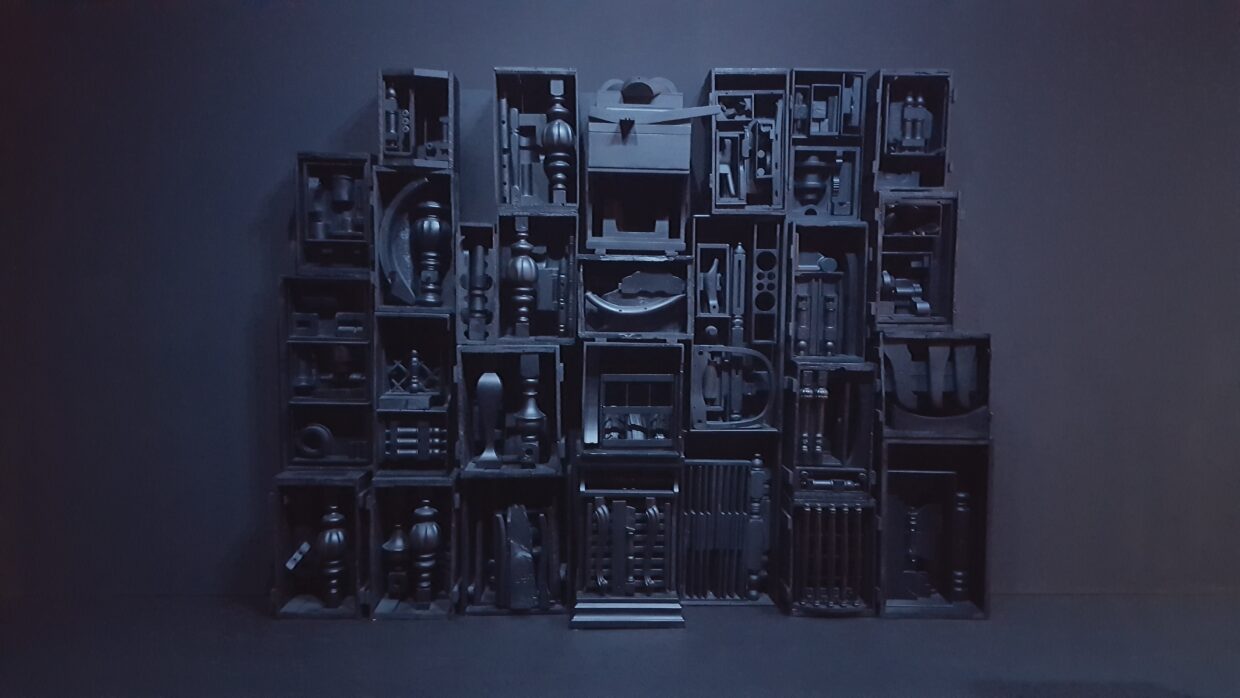

Louise Nevelson, Untitled, 1964. Wood painted black, 8 ft. 4 in. x 10 ft. 11 1/2 in. x 1 ft. 6 3/4 in. (254 x 334 x 47.63 cm). © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Julia Bryan-Wilson.

Louise Nevelson, Untitled, 1964. Wood painted black, 8 ft. 4 in. x 10 ft. 11 1/2 in. x 1 ft. 6 3/4 in. (254 x 334 x 47.63 cm). © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Julia Bryan-Wilson.

JR: Your scholarship is studiously subversive in a lot of ways. You very deliberately and confidently trace the roots of Nevelson’s work to sources outside canonical Modernism. Instead of Picasso and Cubism, for instance, you go to quilts. Instead of Malevich and the monochrome, you go to whitework embroidery. One of the most fascinating taproots you unearth is the blackware ceramics of the Southwest Pueblo cultures. I’m curious to hear about your moment of recognition of the Nevelson/Tewa connection. I assume that’s never been traced before?

JBW: Not to my knowledge, though Nevelson’s admiration for Indigenous ceramics of the US Southwest, including an acquisitive covetousness in her collecting practices, was plain to see. I co-taught a class on Indigenous art of the Americas (with Beth Piatote and Natalia Brizuela) and delved into Maria Martinez’s blackware; her use of geometries and the subtleties of her black-on-black patterning struck me as chiming with Nevelson’s preoccupations with blackness. I was conscious about how to negotiate a politics of comparison, and I made decisions at the level of the image program to intentionally foreground folkloric practices rather than normative high art lineages. Pottery and textiles are the monochromes that I insist upon as forerunners for Nevelson—indeed they predate Picasso and Malevich, whose work I do also mention but have chosen not to illustrate.

This returns us to Janson and how much art history has been deeply sexist. To me the answer to this problem is not simply to include more women artists in textbooks, or to exclude men from them as in Katy Hessel’s popular The Story of Art Without Men. Rather than this reshuffling of proper names within familiar canonical movements, we need to change our definition of art altogether, so that we include objects like quilts by women whose names we may never know or ceramics made by those who did not necessarily call themselves artists but whose work is full of creativity and innovation.

To me the answer to this problem is not simply to include more women artists in textbooks, or to exclude men from them as in Katy Hessel’s popular The Story of Art Without Men.JR: Nevelson famously repurposed used wood in her sculptures. You repurpose and rebut many old art reviews. Interestingly, Robert Hughes isn’t the worst. I wonder if you have any methods or principles around engaging with earlier reviews and criticism? How do you decide what you want to resuscitate in those texts?

JBW: I love this question and it’s true that I found some unexpectedly useful readings of Nevelson’s work by many types of writers. I tried to be non-sectarian in my approach to the criticism because Nevelson had rabid detractors and ardent supporters, and the party lines that emerged around her especially in the 1970s now appear laughably rigid. Masculinist critics I usually dismiss, like Hilton Kramer and Hughes, took Nevelson seriously, while many of the critics affiliated with postmodernism whose work has been very meaningful to me really hated her work.

Her work’s legacy has suffered because of moribund categorizations around formalism and autonomy that were fiercely debated at the time and do not interest me much at all. So, while I draw on the complicated responses of professional art critics of the moment, I look also to alternative sites for interpretation: to her queer fans, to feminist poems written in homage to her, to children’s art inspired by her, to contemporary artists who see her as pivotal for their own work. Those responses are so rich and rewarding because they are so untethered from pretty airless artworld debates.

Louise Nevelson, Untitled, 1981. Fabric, paint, paper, and wood collage on board, 31 7/8 x 20 1/8 in. (81 x 51 cm). Gió Marconi Gallery, Milan. © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Julia Bryan-Wilson.

Louise Nevelson, Untitled, 1981. Fabric, paint, paper, and wood collage on board, 31 7/8 x 20 1/8 in. (81 x 51 cm). Gió Marconi Gallery, Milan. © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Julia Bryan-Wilson.

JR: Down in foundations, the book in many ways undoes the forms and conventions of the artist monograph. I wonder, what led you to the structure? When did the form click? And were there any keywords you discarded?

JBW: I had so many struggles as I came up with this format of four separate but interconnected volumes, which I’m calling a modular monograph. I didn’t want the book to be chronological, since I wanted to honor the consistencies that exist across some thirty years of Nevelson’s sculptural practice. At one point I envisioned a dozen very short chapters organized under the title “12 Questions about Louise Nevelson.”

But that felt too atomized, like a series of hot takes instead of the sustained investigation her art needed. Increasingly, the writing coalesced around the keywords of dragging, coloring, joining, and facing—they are taken from Nevelson’s own sculptural procedures but have many other resonances. I was inspired by the boxy modularity of Nevelson’s work and had a vision of a slipcased format that would echo it. Then I had to convince my publisher to take this risk with me: not easy.

When I held the physical copy in my hand for the first time, I realized just how much agency I had relinquished. The instant the volumes slid out of the case I thought: people really are going to read these in any order! It was a thrilling and terrifying moment. I have given up the orienting introduction. I have given up the ordering logic of chapters. I have given up the comforts of a conclusion.

But I strongly believe that in order for art history to move beyond its own conservative tendencies, we have to push at or break apart its cherished conventions. I see it as a feminist strategy and a queer strategy to undermine the authority of the vaunted category of the monograph with all its weighty significance. Though I worry the four volumes will feel confusing, this insistently tactile interface is meant to bring the reader back to Nevelson’s own process. It is also meant as a comment on the partial nature of history itself, which always comes to us in fragments.

JR: Nevelson’s public image poses an interesting problem for you. She was such a strange and recognizable figure in the mid-century American artworld, almost a 19th-century spiritualist apparition, to the point that her persona in some ways eclipsed her art. I found it so interesting, your internal debates about representing her self-representation. Were there any significant conversations that convinced you to go ahead and include her image in the book? Maybe talk about the debate around showing her image.

JBW: Yes, Nevelson was hugely famous as a kind of flamboyant grand dame of bohemia – her shawls and eyelashes were as discussed as her sculptures. I wanted to grapple with her still under-studied artistic work but also reckon with her overexposure as a personality while not letting her outfits take over, as they tend to do. Some of her obituaries say more about her makeup and attire than they do about her towering achievements in US sculpture.

At a certain point I was so frustrated with the attention paid to her looks. Nobody is obsessing about the clothes of male artists like Ad Reinhardt! During my research phase, I gave a few preliminary public lectures declaring that my book would have zero photographs of Louise Nevelson; this was meant as a feminist polemic to stop collapsing her art onto her body. To my surprise, the loudest voices against this strategy came from older women who recognized that Nevelson’s aged face was its own form of defiance. In a world that silences and suppresses women—and shames us relentlessly for aging—her insistent wrinkles and fierce gaze came to be critical to me as a vector of analysis.

In a world that silences and suppresses women—and shames us relentlessly for aging—her insistent wrinkles and fierce gaze came to be critical to me as a vector of analysis.JR: You also insert yourself in the book in many subtle and fun ways. The art historian shows her face, so to speak. How big of a deal is that in the discourse of academic art history?

JBW: I think it’s less and less of a taboo for the art historian to speak from their own investments—and within feminist art history and queer theory that has long been a crucial strategy. For me it’s a balancing act—the lens of the personal can be a generous route in for some readers, but a focus on my individual experience can also be limiting. This is not a memoir, but it does investigate, from the situated stance of my own embodiment, how Nevelson’s work might be relevant today—indeed, more relevant than ever.

Louise Nevelson, Frozen Laces-One, ca. 1979–80. COR-TEN steel painted black, 103 x 65 x 48 in. (261.6 x 165.1 x 121.9 cm). Allen Center, Houston. © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Julia Bryan-Wilson.

Louise Nevelson, Frozen Laces-One, ca. 1979–80. COR-TEN steel painted black, 103 x 65 x 48 in. (261.6 x 165.1 x 121.9 cm). Allen Center, Houston. © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Julia Bryan-Wilson.

JR: The book ends, if you choose to read it in a certain order, with a visceral appreciation of living trees. Nevelson’s blackened wood medium becomes a harrowing prophecy of incineration. Not to give anything away, but did you know the book was going there from the beginning, or did circumstances collude to bring you to that coda?

JBW: I had no idea when I set out to write this book that I would end up in climate crisis and forest fires, though now with the benefit of hindsight it feels inevitable. I did often pause to wonder what exactly was drawing me to her sculpture, given that I worked on this book for nearly a decade and it took me all the way to rural Ukraine to see the trees of Nevelson’s childhood (her father and her grandfather both worked in the lumber trades).

But I could never really answer that question—why Nevelson?—until I was up against the deadline to complete the manuscript in fall 2020, and instead I was paralyzed with the quite legitimate fear that my own small wooden house in Oakland would burn down. This a time when fires were raging through northern California; the sky was orange from smoke and finishing the book was impossible. Yet I kept turning to her sculptures, the same ones I had been studying for years, to try to process this destruction. Then I realized that what I had been doing all along was thinking with and through wood.

__________________________

Julia Bryan-Wilson’s Louise Nevelson’s Sculpture is available now from Yale University Press.