In 1975, four years after the release of The French Connection, William Friedkin revealed to a reporter the inspiration for the film’s celebrated car chase scene.

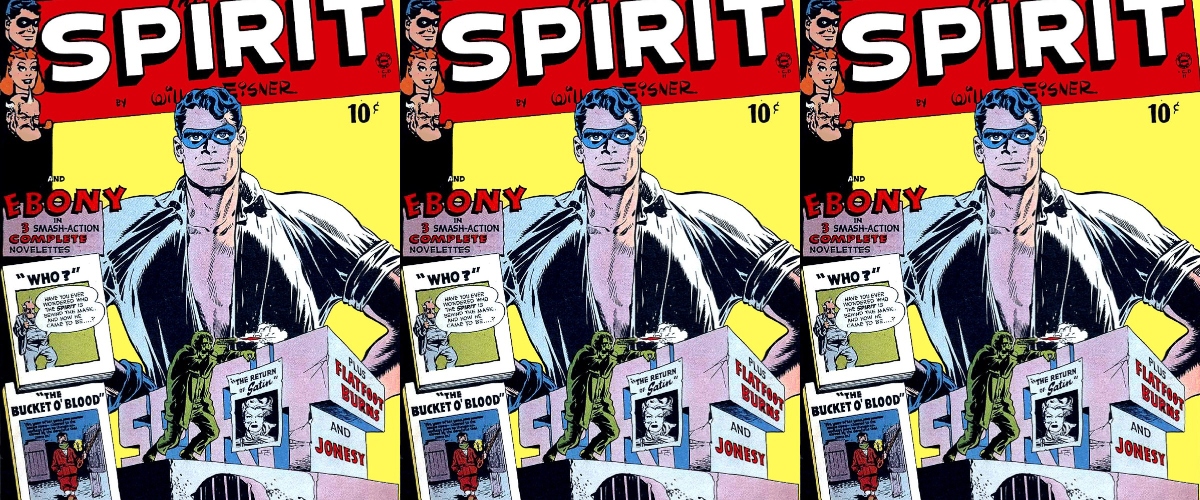

It was the cover of a comic book: a man runs terrified on elevated tracks, just a few steps ahead of a train. He is handsome and athletic. Save for a domino mask, he is dressed like a classic Hollywood detective, in a blue suit and loose tie; he bears no resemblance to Gene Hackman’s slovenly everyman “Popeye” Doyle. The cover was from The Spirit, a comic that ran as a seven-page newspaper insert throughout the 40s and early 50s. The series, created by Will Eisner, was admired for its black humor, innovative compositions, shocking violence, and its setting in a precisely realized urbanscape. “Look at the dramatic use of montage, of light and sound,” Friedkin told the reporter. “See the dynamic framing that Eisner employs, and the deep, vibrant colors.”

Friedkin may not have been telling the truth. The comic he showed the reporter was a reprint that had been published after the release of The French Connection. The stories were three decades old, but the covers were new. Still, it was good publicity for the project he was then planning, a feature-length pilot for an NBC series that would feature the Spirit, aka Denny Colt, a detective who has risen from the dead, lives in a cemetery, and fights crime with his wits, his fists, and a willingness to withstand pain that borders on masochism.

Eisner and Friedkin shared a sensibility, particularly an instinct for fatalism. In The French Connection, “Popeye” Doyle, whatever his talents as a detective, is undone by obsession. Friedkin’s other characters—the self-loathing gay men in The Boys in the Band, the mother who fights for her devil-mutilated daughter in The Exorcist—are entrapped, left to shout against themselves or God. In the mid-70s, following the success of The Godfather movies, Mario Puzo started writing the screenplay for Richard Donner’s Superman, which would be released in 1978. If Friedkin had made The Spirit, he would have created a different template for today’s most dominant genre.

At the time of that interview, Friedkin was developing the project with Pete Hamill, a crime writer and columnist. Hamill’s best work as a screenwriter was uncredited; he had provided the dialogue for John Frankenheimer’s sequel to The French Connection. In the film’s set piece, “Popeye” Doyle suffers a breakdown and rhapsodizes about a failed baseball career. In a primal, halting monologue, Hackman reveals the infantile rage of a man committed to a life of violence.

Hamill approached the Spirit with the same pathos. In a sketch, he maintains much of Eisner’s original vision, including the Spirit’s signature habit of tripping and falling down stairs when chasing criminals, and his melancholic sense of humor. He “often seems uncomfortable in his own body, as if its size forces him into physical action when he would rather just go to the beach,” Hamill writes. The superhero who wants to go to the beach is usually played for cheap laughs. Hamill understands the character as high tragicomedy.

If Friedkin had made The Spirit, he would have created a different template for today’s most dominant genre.Hamill wrote three disparate treatments for Friedkin, all of which were rejected. The first two anticipate the better superhero movies and cartoons of the last few decades. The third is among the many unproduced science-fiction epics—possibly brilliant, far more likely terrible—that make up the shadow history of cinema.

The First Treatment

There’s always the problem of realism. In theory, it’s impossible to go too far in a superhero story. The question is how much restraint you exercise to make sure the viewer believes the narrative. How vulnerable is your hero? How apocalyptic the threat? Do you really care if the science is accurate? Like many comics storytellers, Hamill solves the problem with metafiction.

Hamill knows when to be loyal and when to be disloyal. As in Eisner’s original comics, Denny Colt, an Irishman who speaks in Yiddish slang, has roots in the outer boroughs. But whereas the original comics depict the Spirit’s sidekick, Ebony White, as a minstrel with simian features, the treatment describes a street-smart and regular smart 12-year-old. In the comics, Eisner’s characters often break the fourth wall; they know they are heroes in a comics story. The treatment entertains a similar strategy, casting the two leads as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Colt and Ebony study comics books, just as their predecessors study the tales of chivalry.

The villain is Richard Abrams, a sexually frustrated teenager who also treats comics as a guidebook, both to develop his mad scientist persona and to pursue his nefarious scheme (in his case to miniaturize the island of Manhattan). In a note, Hamill suggests a young Jules Feiffer, who had written several Spirit stories in his youth, as the villain’s physical model.

Feiffer could have been the model for Abrams’s character as well as his physique. Like Abrams, Feiffer was a comics obsessive. He had studied Eisner’s work for years before walking into his studio at the age of 17, looking for a job. He later became famous for a syndicated strip, in which he documented the travails of a generation of men and women for whom the sexual revolution came just a few years too late. His characters were as lovable as they were fundamentally broken. Accordingly, Hamill wants to make Abrams “as sympathetic as possible, to break the stereotype, and also to make the audience kind of root for him, wishing they could do the same thing…”

Hamill may not have known that Federico Fellini had considered making a superhero movie himself.We have seen much of this since: the Don Quixote approach, the villain as nerd gone bad. It is a humane take on the genre. In Hamill’s first treatment of The Spirit, the hero tries to be better than he is, and the villain a grander version of himself, both hoping to realize an ideal of heroism and villainy in a civilization too dull to accept either.

The Second Treatment

The second treatment is neo noir, a meditative odyssey, as Denny Colt, having risen from the dead, investigates the mystery behind his own father’s death.

In this version, New York is nearing the end of history. A retired hitman “works as a custodian in an abandoned synagogue in Brownsville, a lone white man in a sea of blacks.” At the abandoned Lyceum, “a troupe of ancient actors perform each night in secret, only for themselves, with scratchy phonograph records playing the music of the past.” Colt visits a radical chic party, a Voodoo cult, a crooked nursing home run by an “evil rabbi” (a reference to the Bernard Bergman case, one of 1975’s sensational crime stories), and a high-class brothel. I want to see this movie, even if it is a little too comfortable with racist and anti-Semitic tropes.

The treatment gives Friedkin plenty of opportunity to indulge his talents. There’s a car chase across the Triboro Bridge into Flushing, and a fight with albino alligators in a sewer beneath the Metropolitan Museum of Art. But in his note to Friedkin, Hamill lays out a theme regarding the nature of identity. “As he plunges deeper into the mystery of the search, this man with a literal mask should be removing the mask of everyone he encounters.” He suggests La Dolce Vita as a model.

The Spirit, who wore a suit instead of tights and who tripped over his toes, was an anti-superhero, loved by readers who knew the genre was capable of literary merit.Hamill may not have known that Federico Fellini had considered making a superhero movie himself—his was to have been an adaptation of the strip Mandrake the Magician starring Marcello Mastroianni. Either way, the treatment imagines the kind of superhero movie Fellini might have directed. This version of The Spirit is a carnival of grotesques, which the hero journeys through, at times as a detached, self-assured observer, at others a reluctant participant in a decadent society.

The Third Treatment

In Hamill’s third treatment, Denny Colt is not a detective, but an environmental engineer, who awakes from a cryogenic chamber into a post-capitalist dystopia. He takes up the identity of the Spirit, which he constructs out of historical records of crime and policing. This is the least bizarre aspect of the narrative.

Corporate powers took over the government sometime in the 70s and made environmentalism illegal. Now the mass of humanity lives within artificial cities made of giant red orbs—called “Urbs”—within which the past Earth—everything from Chinese restaurants to Arab bazaars—has been reconstructed in an antiseptic, machine-governed environment. Sex androids satisfy the carnal needs of humanity. Jousting tournaments with giant vehicles satisfy their entertainment needs. The exterior world is threatened by a giant fog of pollution and fetid sludge. The general area is known as Central City—the name Eisner gave the Spirit’s home in the original comics—but the Urbs occupy the ruins of old New York, and it is cut off from the rest of the world. An underground resistance made up of antediluvian religious zealots occupies catacombs beneath the surface.

Friedkin was the rare showman who knew as much about human suffering as he did about spectacle.This is the kind of cultural artifact that belongs in the category “What occasioned this?” There is nothing in the treatment that speaks to Hamill’s style or interests. It has nothing in common with Eisner’s original series, not even the subpar science-fiction stories of its final years. Friedkin knew how to build terror in claustrophobic environments, so who knows what he could have done inside these “Urbs.” But the horrors Hamill describes lack the wit and the internal logic of The Exorcist. Friedkin did not practice the cinema of excess in which every inch of the screen is filled with detail, far more than the average viewer can absorb or study. This is all a long way of saying the treatment has nothing to do with Friedkin as well, and I have no idea what Hamill was thinking.

The Spirit, who wore a suit instead of tights and who tripped over his toes, was an anti-superhero, loved by readers who knew the genre was capable of literary merit, the same readers who would devour Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns in the 80s. But there are only so many genre conventions you can break before you lose everything you liked about it in the first place.

*

Hamill gave up on trying to please Friedkin, and over the next two years the director would enlist three other prominent writers for the project: Jules Feiffer, Harlan Ellison, and Eisner himself. Like Hamill’s third treatment, Feiffer’s is a bizarre mix of bad anti-capitalist satire and 70s dystopia, with a touch of Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle. (“I must have been going through some kind of crisis at the time,” he wrote me when I sent him his version.) Ellison’s revives Ebony White’s minstrel persona. Eisner’s updates the better aspects of his original comic, but the treatment lacks passion. Friedkin moved on.

In the early 80s, Brad Bird, then a recent graduate of the California Institute of the Arts, attempted to make an animated feature film based on The Spirit, and he produced a three-minute pencil test. The piece utilizes the strategies of live-action film, looking back to the Superman cartoon series of the 40s, and anticipating Batman: The Animated Series and Bird’s own masterpiece, The Incredibles. It’s impressive work, but animated features were not popular at the time, and he failed to obtain financing.

There would be two live-action adaptations, the first a two-dollar-budget television pilot for ABC, starring Sam J. Jones, who had played Flash Gordon in a fun as high heaven glitzy adaptation a few years before. This version is heterosexual camp—a love interest admires the Spirit’s shoulders even as she compares him to Charles Manson—and maybe it could have worked, but unfortunately, no one is intelligent enough to sell a word of dialogue. It aired once, during rerun season, buried on a Saturday night in July 1987.

In 2008, Frank Miller, Eisner’s friend and arguably his protégé, directed a theatrical adaptation, shot entirely on green screen. Gabriel Macht plays Denny Colt as a dumb jock. Samuel L. Jackson plays the arch-villain. He wears a samurai suit, and later on a Nazi uniform, and he kills kittens, and it’s all more hateful and joyless and stupid and cruel than it sounds.

“One might argue that the consistent inability to translate The Spirit to live action is testimony either to Eisner’s talents or to the intrinsic way The Spirit depended on the media form it was depicted in originally,” Paul Levitz, the author of a book about Eisner, wrote me. He suggests a version of the film, made in the 40s, starring an Arsenic and Old Lace Cary Grant, might have been successful.

In 2019, Martin Scorsese penned a New York Times op-ed, in which he described what he searched for in cinema as a young man and what the superhero blockbusters of our current era lacked. The great films of the 40s and 50s, he wrote, were “about characters—the complexity of people and their contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures, the way they can hurt one another and love one another and suddenly come face to face with themselves.”

That was the Spirit in Eisner’s comics, and in Hamill’s second, Fellini-esque treatment, which, ideally, would have starred Roy Scheider. For Hamill, the Spirit’s immortality is a curse. His desires for justice, order, love, and human connection are confused. His city is already fallen and it can never be saved, only managed. Superhero fans will point to any number of films that depict similar heroes and similar worlds, and they’re not all bad. (I like, but do not love, Logan.) But Hamill’s take on The Spirit would have been sadder and better. Friedkin was the rare showman who knew as much about human suffering as he did about spectacle, and you would have believed the Spirit’s pain as much as you did his powers.

*

Special thanks to Caroline Jorgenson, of the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, who obtained scans of Pete Hamill’s treatments for The Spirit. Denis Kitchen provided copies of Will Eisner, Harlan Ellison, and Jules Feiffer’s treatments, as well as Eisner’s notes to Feiffer.