How Annie Ernaux Captures the Spirit of Her Era Through Its Big-Box Stores

In Conversation with Alison L. Strayer, the Translator of Look at the Lights, My Love

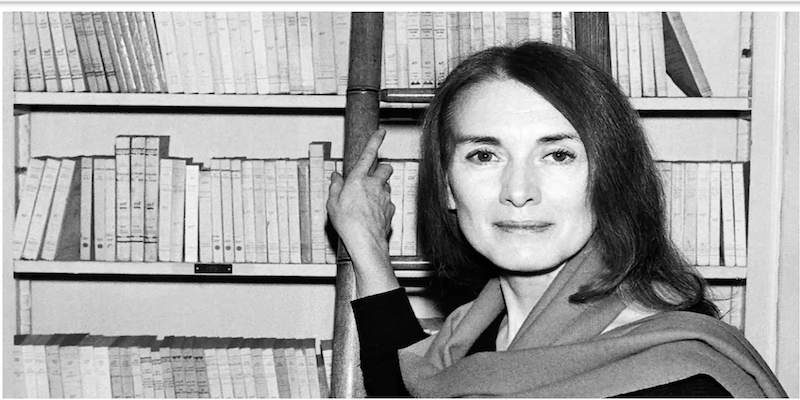

Alison L. Strayer is an award-winning writer and translator. Her work has been shortlisted twice for the Governor’s General Award for Literature and for Translation. Her translation of Annie Ernaux’s The Years was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2019 and won the French-American Translation Prize in the nonfiction category as well as the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation, honoring both author and translator.

*

Tell us about your experience as Annie Ernaux’s longtime translator. When did you first encounter her work, and what drew you to it?

I have translated the books of Annie Ernaux for seven years. The first was Les Années (The Years), starting at the end of 2015.

The very first time I encountered her work was in 1992, when I was still living in Montreal. I was given Passion simple (Simple Passion) as part of a script-editing job. The filmmaker-screenwriter had been very inspired by Passion simple (though the film was not based on the book) and he wanted his film to have the same “feel” as Ernaux’s writing. Passion simple is the first book in which Annie Ernaux relates her relationship with a married Soviet diplomat; Getting Lost is the diary of the two-odd years that affair lasted.

I read Passion simple in one sitting. The story spoke to me, and I was struck by how spare the writing was. I wondered throughout how she managed to tell the story of that fraught situation with such directness and economy—and no melodrama.

With every book by Annie Ernaux I read thereafter, I continued to ask myself, “How did she do that?” I appreciated and was fascinated by the author’s simultaneous endeavor to tell the story, and seek a way of telling it which will allow her to get as near as possible to “what happened.”

Last but not least, on reading Passion simple in 1992 I was very curious as to how it would read in English. I tried translating a few paragraphs and discovered that there was a big difference between translating the words and capturing a voice.

With The Years, this part of the work was, in my perception, similar to laying down one stone next to another on the ground—stone after stone (marking out, perhaps, a wall) and the stones were words.I didn’t read Tanya Leslie’s wonderful translation of that book, and others, for another eight years or so.

*

How do you balance direct translation and artistic rendering in your translations?

With every book I’ve translated in the past fifteen years, I have aimed for “closeness to the original” (though that is probably a very tired turn of phrase). This said, I’m aware that the notion of “closeness to the original” can be—is—interpreted in different ways by different translators. It is always interesting to see how each approaches the question.

Certainly in Getting Lost, and later in Look at the Lights, My Love, I was guided by different things the author herself has written, for example:

I neither altered nor removed any part of the original text while typing it….For me, words set down on paper to capture the thoughts and sensations of a given moment are as irreversible as time—are time itself. [from the intro to Getting Lost]

And:

I am convinced that the syntax, the rhythm, the choice of words correspond to something very deep, where the marks of multiple learning and what relates to the writer’s life story are combined. [from L’écriture comme un couteau, p. 89, my translation]

I start by doing a very basic rendering (which I continually refer to, along with the original text, for a very long time in the process).

I adhere to the sentence structure of the original, choosing words—say, nouns—of the same register, or even length of those in the original (that is, I try not to fancy them up, though spontaneously I may have another word in mind). I end up with a sort of “footprint” (as you might say of a house you had torn down or were going to put up), an imprint, as a starting point. For instance, with The Years, this part of the work was, in my perception, similar to laying down one stone next to another on the ground—stone after stone (marking out, perhaps, a wall) and the stones were words.

This first “heavy” draft remains a guide throughout the many later drafts. It is anchored in my memory, and in my body.

At a later stage, the “voice” of English and the rhythms of English makes themselves felt, and draw me out of the heavy rudimentary drafts.

I’ve mostly used The Years as an example above, but I worked in the same way while translating Look at the Lights, My Love.

*

What was it like to translate Look at the Lights, My Love?

Well, I enjoyed it. The subject matter certainly appeals to me, as I am, or have in the past been a real shopping mall/shopping district flâneuse. Not for the sake of buying anything, just seeing what is there and losing myself in that environment.

Look at the Lights, My Love is a journal of observations containing a wealth of very precise descriptions—of the premises, including its design, methods of entry, exit and circulation, the merchandise and its staging, the customers (different depending on the day and the time of day), the frequent and spectacular changes in décor, promotions, etc. over the many holidays, seasons and special events of the year (including, for example, Chinese New Year and Ramadan).

The primary function of the book is to convey information—to serve as a record—and this dictated the approach to translation. Precision is very important.

I also very much enjoyed doing the research for the specialized vocabulary—e.g., shopping center design, the checkout robot-voice scripts, the precise wording of warning signs, the names most commonly used for products and departments, promotional buzzwords and so on.

There were a few specific vocabulary issues. For example, big supermarkets in France are often called “hypermarchés” (that is Ernaux’s word), which I’ve translated as “hypermarket” in the past. It works for the U.K. editions and the U.S. editor has usually agreed to the use of that word, too. In the end we decided on “big box store,” “superstore”—”supercenter,” too.

*

Look at the Lights, My Love is a meditation on the big-box superstore as “a great human meeting place, a spectacle.” How does this meditation differ from Ernaux’s autobiographical work?

First of all, this is a very autobiographical work. It simply explores a different approach to autobiography. (Ernaux sometimes calls auto-socio-biographie.)

Look at the Lights, My Love has very clear family ties with other works in the Ernaux oeuvre, for example, two earlier “journaux extimes,” to borrow the expression of Michel Tournier—”journals of the outside.” The titles of those earlier books are Exteriors and Things Seen. Unlike the inward-focused journal intime (a personal diary) the journal extime is outwardly focused, captures something of the times, of life as it is lived collectively, but of course, it also inevitably paints a portrait of the person who’s writing down the details of that outside world.

In Exteriors (originally Journal du dehors, which covers the years 1985-1992, translated by Tanya Leslie in 1996) and Things Seen (La vie extérieure, covering, 1993 to 2000, translated by Jonathan Kaplansky in 2010), she describes scenes, people, products, ads, graffiti—signs of the times—observed in or from commuter trains, in shopping mall supermarkets and other stores, hair salons, streets.

In Look at the Lights My Love, Ernaux reflects, “We choose our objects and our places of memory, or rather the spirit of the times decides what is worth remembering.” She goes on to wonder at the fact that superstores are only starting to be recognized as “places worthy of representation” in books, films, etc. and recalls numerous scenes from her own life that have taken place in big-box superstores and shopping malls.

In many of her books, indeed, there are scenes of shopping centers, grocery stores, department stores, and so on. They are instrumental, for example, in A Girl’s Story.

*

Do your experiences in big-box superstores resonate with Ernaux’s? What emotions or thoughts have big-box superstores evoked for you?

Definitely. For most of my life I have been a city walker, and certain stores or shopping centers or shopping streets have provided the necessary incentive or sense of anticipation to get me out of the apartment after a work day to make the transition between inside and outside.

(Annie Ernaux writes about this in Look at the Lights, My Love—stopping by Trois-Fontaines shopping center and Auchan is a treat and sort of celebration when the writing day has gone well. During solitary sojourns in other towns where she has gone to write, a trip to a shopping center is her moment of reuniting with the world, etc.)

The kind of big-store flânage which Ernaux describes in Look at the Lights, My Love is very compatible, I find, with translating. I sometimes find myself testing out a problem sentence or word in a different way when my consciousness is the way it is in a vast commercial space—partly neutral, even slightly dazed, partly engaged by a specific sight or object, and sometimes, if only distractedly, still working, though with more leisure than when I am at my desk.

In Look at the Lights My Love, Ernaux reflects, “We choose our objects and our places of memory, or rather the spirit of the times decides what is worth remembering.” She goes on to wonder at the fact that superstores are only starting to be recognized as “places worthy of representation” in books, films, etc. and recalls numerous scenes from her own life that have taken place in big-box superstores and shopping malls.For me, the prospect of buying items needed for an evening meal, or a new notebook, or even a newspaper, serves the same purpose (a pretext, a lure) as the lead pencil Virginia Woolf strikes out to find by way of a rich and circuitous path in “Street Haunting” (that brilliant, thrilling essay, so full of appetite and desire, which reminds me so much of certain passages in the writing of Annie Ernaux!).

*

Where is your favorite place to read a new book by Ernaux?

My favorite place to read Annie Ernaux is in the Paris metro or commuter trains, or on long bus rides. So many scenes in Ernaux’s books take place in and around metros and trains and stations.

*

In 2022, Annie Ernaux received the Nobel Prize for Literature. She was the 17th woman out 119 laureates in the award’s history. What impact do you hope her award will have on women writers and translators around the world?

In the books of Annie Ernaux, there is a palpable, deeply felt connection between women’s rights and women’s writing.

In her Nobel lecture she wrote:

This commitment through which I pledge myself in writing is supported by the belief, which has become a certainty, that a book can contribute to change in private life, help to shatter the loneliness of experiences endured and repressed, and enable beings to reimagine themselves. When the unspeakable is brought to light, it is political.

We see it today in the revolt of women who have found the words to disrupt male power and who have risen up, as in Iran, against its most archaic form. Writing in a democratic country, however, I continue to wonder about the place women occupy in the literary field. They have not yet gained legitimacy as producers of written works. There are men in the world, including the Western intellectual spheres, for whom books written by women simply do not exist; they never cite them. The recognition of my work by the Swedish Academy is a sign of hope for all female writers.

I feel that Annie Ernaux’s recognition by the Swedish Academy will have a positive impact on women’s writing and its translation, with the participation of an increasing number of publishers (I believe) who are open to hearing from, or who are actively looking for these authors, works, and translators.

______________________________

Annie Ernaux’s Look at the Lights, My Love is published this month by Yale University Press in its Margellos World Republic of Letters translation series.