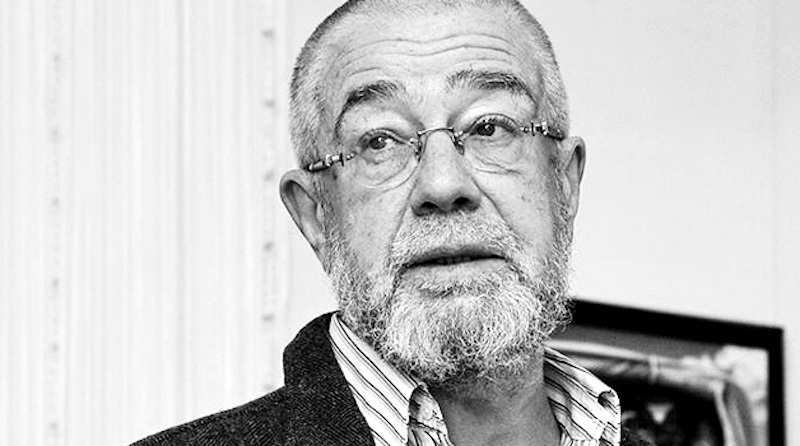

Why the Russian Protest Poems of Sergey Gandlevsky Still Matter Today

Phillip Metres on Political Literature, Classical Forms, and What Outsiders Get Wrong About Russian Poetry

In 2016, Sergey Gandlevsky was arrested and detained by Moscow police after tearing down a poster of Stalin on the wall in the Lubyanka metro station. Lubyanka is the notorious neighborhood that housed the Soviet secret police. It is now home to Russian security services. “I tore it off the wall,” Gandlevsky said, when asked by a journalist, “because [Stalin] is a criminal.”

After being threatened with imprisonment for vandalism and petty hooliganism, Gandlevsky was released without charge. The Soviet Union has been dead for over thirty years, and Stalin’s crimes disavowed by the Soviet Union in the 1960s, but it is as if history is repeating itself in Russia. “Everything that’s happened to us will happen again,” as Gandlevsky once wrote in a poem, not knowing how it would come true.

Despite his detention, Gandlevsky has never been, strictly speaking, a political dissident. He has always been, first and foremost, a poet. But in an unfree society, to be a poet, Gandlevsky believed, required refusing to participate in a system he believed was morally bankrupt. At a bilingual reading with Gandlevsky, someone asked why I decided to study Russian language and poetry, I said that I heard Reagan call the Soviet Union “the Evil Empire,” and I thought Reagan was wrong—that a whole country could not be evil. Gandlevsky replied, “when I heard Reagan say that, I thought he was right.”

Sergey Gandlevsky was born in Moscow in 1952, one year before Stalin’s death. An integral figure in the Russian underground poetry scene in the 1970s and 1980s, Gandlevsky began writing poetry only for himself and his friends. In 1972, at Moscow State University, Gandlevsky co-founded Moscow Time, a poetry group which included fellow comrade-poets Alexander Soprovsky, Aleksey Tsvetkov, and Bakhyt Kenjeev, until Tsvetkov’s emigration in 1974. (Gandlevsky would later elegize all of these poet friends in verse.)

Critic Lena Trofimova recalls how Moscow Time’s “poetic fraternity opposed the official literary studio of the university, who had all the necessities of a comfortable but a conformist existence—good lodging, financial support, organized regulations of study.” When asked about Moscow Time’s aesthetic position, Gandlevsky laughed and said:

Since we are talking about three or four extremely funny young people who are always drunk, this very idea would have caused a surge of drunkenness and laughter. There were, of course, reasons of the most general, ideological order. We were all idealists. We believed that death is not the end. We did not believe that there is no purpose in life and that the Universe is a confluence of some molecular circumstances. We did not treat poetry as a mere human activity: one stitches boots and the other writes in rhyme. At the same time, after all, we were scoffers, so the priestly pose in its pure, symbolic form was not welcomed.

Unlike the Sixties Generation of Russian poets—most notably, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Andrey Vosnesensky, and Bella Akhmadulina—who embraced the role of the poet as public figure of political conscience and performed readings for thousands of people, the Seventies Generation saw the limits of poetry as public dissent. The trial of poet Joseph Brodsky in 1964, the show trial of writers Yuli Daniel and Andrey Sinyavsky in 1966, and the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 ended the Khrushchev Thaw.

In an unfree society, to be a poet, Gandlevsky believed, required refusing to participate in a system he believed was morally bankrupt.With the ongoing reassertion of the Communist Party in the Brezhnev era, the elder generation of poets looked morally compromised to the rising generation. Gandlevsky himself had no love for what he saw as the “versified ideas of the middle intelligentsia” of Yevtushenko, and saw poetry as a means of privacy, a bulwark against a politics that had contaminated all aspects of Russian life.

By contrast to the attention-seeking political harangues of the Sixties poets, Gandlevsky and Moscow Time saw poetry as a personal matter. For them, as Gandlevsky writes in Trepanation of the Skull, “There was no one whose eyes had to be opened or who had to be made to understand [about the wickedness of the Soviet Union]. Everyone knew everything without that.”

In the 1970s and 80s, during the twilight years of Soviet empire, Gandlevsky worked odd jobs—night watchman, theater stagehand, museum docent, and train cargo guard—opting out of the system of relative privilege afforded to writers who played by the rules. As internal émigrés, poets who had opted out of the “official” path of Russian writers during the Soviet period, Gandlevsky and his generation forged new directions in Russian poetry—often by reasserting links to suppressed or forgotten Russian poets whose emphasis was on aesthetic freedom over political engagement.

Gandlevsky and other poets of the underground did not appear in Russian literary journals until the late 1980s. Since then, with the fall of the Soviet Union, Gandlevsky’s work has received nearly every major Russian literary prize; he has won the Little Booker Prize (1996), the Anti-Booker Prize (1996), Moscow Score prize (2009), and the Poet Prize (2010). A Russian critics’ poll in the 2000s named him the country’s most important living poet.

While Gandlevsky continues to write poetry, the poet-Soviet period rhymed with the poet’s expansion of his literary repertoire into drama, critical essays, memoirs, and novels. His work has been translated into numerous languages and has been included in nearly every major English translation anthology of Russian poetry since the early 1990s. The first volume of his selected poems translated into English, A Kindred Orphanhood, came out in 2003 from Zephyr Press, followed by two narrative prose works translated by Suzanne Fusso, Trepanation of the Skull (Northern Illinois University Press, 2014) and Illegible (Northern Illinois University Press, 2019).

If the affiliations of Seventies Generation provide a cultural context of the Soviet stagnation period, they don’t describe what’s distinctive about Gandlevsky’s verse. Gandlevsky writes in strict rhyme and meter, in what is known in Russian poetry as classical form. Gandlevsky once said that classical form was “given to me by birth…there really wasn’t any choice for me in this regard.” Gandlevsky’s employment of classical form was, in some sense, a return to a Russian poetic tradition that had been buried by Soviet imperatives.

Yet the classical verse tradition and its rhyme and meters remain a standard feature of Russian poetry, long after modernism staked new pathways in American and European poetry. Where Gandlevsky’s poetry distinguishes itself is in how the classical form and ordinary, degraded life collide, a convergence that Mikhail Aizenberg has called the “explosive mixture” of Gandlevsky’s verse. In the words of poet and critic Lev Loseff, what makes Gandlevsky’s work so pleasurable is that he transforms, with minimalist means, the squalid into music:

Gandlevsky turns the monotony and squalor of Soviet/post-Soviet life into lyrical poetry of the highest probe, and the means by which he achieves it are utterly minimalist. If one has a dream in his poem, it is a dream about fixing an old shed and not having matches to light a cigarette. His diction is almost as mumbling and cliché-ridden as a conversation in a crowded commuter train. His verse forms strictly adhere to the versification rules of a middle-school textbook: iambic pentameter or iambic hexameter for meditative poems, anapest for more sentimental lines. Yet, I repeat, nothing finds a more direct way to your heart than these flotsam and jetsam of the commonplace carried by regular iambic or anapestic waves.

Reminiscent of American confessional poetry, which seethed with fact under the hard artifice of form and allusion, Gandlevsky’s poetry works precisely through yoking oppositions—between form and content, between high concerns and daily indignities. The traditional themes of poetry—obsession with language, freedom, death, love—emerge against the backdrop of a depiction of a vulgar life scarred by alcoholism, debauchery, and ennui.

If there’s something that most outsiders get wrong about Russia and Russian literature, it’s that they presume Russians are obsessed with misery, suffering, and death. On the contrary, Russian poetry is a master class in enchantment, playfulness, and ecstasy. As I’ve written elsewhere, the music of Russian poetry is enchantingly joyful, even ecstatic. It is in their poetry that we can witness the pleasures of a people stereotyped by the West as morbid depressives. It is, indeed, what makes translating Russian poetry most challenging, and why readers of Russian poetry in translation tend to absorb only a vision of a grim and absurd reality but not what it sounds like to have such pure music collides with the grim or the absurd.

If there’s something that most outsiders get wrong about Russia and Russian literature, it’s that they presume Russians are obsessed with misery, suffering, and death.Translating this explosive cocktail is no easy task. For one, Russian poetry’s longstanding tradition of classical form and its adherence to meters is aided by features of the Russian language—its regularity of conjugations and declensions, its flexibility of word order, and its multisyllabic words offer the Russian poet a capacious and seemingly inexhaustible treasury of rhyme and meter in which to play. In contrast to most American poetry, which a century ago threw off formalism as if it were an outworn girdle, Russian poetry still enjoys the rigorously erotic pleasures of form’s confines. (There are, of course, glorious outlaws in both poetic traditions.)

While my initial attempts to translate Gandlevsky often leaned toward accuracy of meaning over fidelity to a poem’s music, Gandlevsky’s later work encouraged me to loosen up my technique and take greater risks for the purpose of song. After all, Gandlevsky was no Social Realist, but a bohemian, vodka-fueled, descendant of Pushkin. My translations, as a result, ride on a ghost of meter and rhyme, carrying the voice and vision of this distinctive Russian poet across the borders of English.

The tone of Gandlevsky’s poems combines humor with world-weariness, but the speakers of his poems are quite masculine. Gandlevsky’s poems occasionally perform a wounded bravado, a weary machismo. But just as the American confessional poets often play with the ruse of unmasking, Gandlevsky’s poems are not simple autobiographical confessions. Gandlevsky once said that though his poems “underline the biographical,” his memory “is cunning, not simple-hearted, and very selective.”

In a poem like “To land a job,” Gandlevsky masterfully combines classical form with a portrait of a rogue, which may or may not be Gandlevsky. Echoing the song “Bolshoi Karetny” by the gutter-voiced Vladimir Vysotsky and Sergei Esenin’s “Letter to My Mother,” the poem reads like A Portrait of the Artist as a Lumpenproletariat:

To land a job at the garage

And sing about a black gun.

And not once in ten years

Stop and visit your old mum.

En route from Gazli in the south

After a canister of sour booze

Screw some girlfriend in Kaluga

Leave her when she’s due.

Gaseteria lamb of Wednesdays,

Cod-pea soup on Thursdays.

To vow to a friend at lunch

To rough up a garage owner, then

Surmount the promising hill

Of a thirtieth birthday…

Is the poem a boast? A confession? A portrait of self-degradation? Or does it reside in the Venn center of all three? Dunja Popovic, in an examination of Gandlevsky’s work called A Generation That Has Squandered Its Men: The Late Soviet Crisis of Masculinity in the Poetry of Sergei Gandlevskii, argues that the poem begins in the glorification of masculine depradation, alcoholism, sexual conquest, violence, and criminality. Against the backdrop of conservative Soviet social mores that propped up the Soviet system, the speaker’s messy life could be read as a rebellion against conformism.

Yet as the poem unfolds, the stakes of his irresponsibility grow. He’s not only failing to visit his mother, he’s also drinking rotten liquor and getting a woman pregnant. But even inside this little ballad, he’s turning thirty, suddenly facing the grim landscape of a life of gaseteria lamb, illegal hauls, and treacherous somnolent drives:

At dawn

To drive for black market gravel

And sing the black pistol.

And if you can’t catch that gig, doze,

Your cheek on the steering wheel,

Remembering with gloom and woe

That Mahachkala brawl.

The poem leaves us with an ambiguous image, in which the driver is either sleeping at the wheel of a parked vehicle, or about to head into a fiery crash. Either way, his life is passing gloomily before his eyes, encapsulated in the flashbacks to brutal beatings.

The poem begins in the romance of a carefree male freedom and ends with a fatal narrowing into ruefully recalled violence. Still, the poem’s superabundance of music, its song-within-a-song, makes this portrait of a trucker barreling into the abyss seem more like a blues song or a quick Scorsese movie, inviting us into an intoxicating but ultimately nihilistic romance of a careless existence.

Though the poem’s lyric speaker could be Gandlevsky, I couldn’t help but observe that, in Gandlevsky’s head-spinning memoir, Trepanation of the Skull, a drinking buddy named Misha Chumak visits the poet from Gazli, along with his girlfriend and baby. In Russian poetry. the use of verbal infinitives invites us to read this poem as a dramatic monologue. But then, one could read any poem—and certainly any poem by Gandlevsky—as a dramatic monologue of a fictive self.

This poem aptly demonstrates some of the challenges in translating Gandlevsky. Gandlevsky forces a translator to scramble between retaining cultural particulars, at the risk of losing the American reader, and opting for some American equivalences, at the risk of effacing the original. Years ago, looking for an American equivalent of рыгаловкa, a Gandlevskian neologism combining the words “to belch” and “diner,” I found it while on a bus ride from Boston to New York. Somewhere around 125th Street, I looked up and saw Gaseteria. (Gasterias no longer exists, but it served its purpose.)

In my earlier translation of this poem, I translated the last lines in this way:

And if not lucky enough for this,

To drift off—cheek on the steering wheel—

Remembering gloomily

A brawl in the Caucasus.

The new version restores some of the rhyme throughout the poem and reasserts the place name of Mahachkala, and the assonance of “Mahachkala” and “brawl” approximates more closely the music of the Russian line.

Gandlevsky’s poetry does not politely invoke the great writers, but rather brings them alive to wrestle with their incomplete legacy.Gandlevsky’s spiritual quest might evoke images of the Beats for the American reader, but for the Russian reader, one hears more keenly the sounds of and allusions to Russian literature. When reading Gandlevsky, a Russian might hear echoes of Pushkin’s measured lyric delight, Chekhov’s alternating atmospheres of gloom and grace, Blok’s foreboding symbolism, Mandelstam’s dark paranoiac urgency of the Voronezh years, Okudzhava’s melancholy songs of Old Arbat, Vysotsky’s gutteral visions, Nabokov’s plaintive nostalgia for his lost Russia, and Tolstoy’s argument with God.

Gandlevsky’s conversation—at times, his argument—with tradition is something that we may only vaguely discern, just ghostly demarcations. Still, Gandlevsky’s poetry does not politely invoke the great writers, but rather brings them alive to wrestle with their incomplete legacy.

*

Despite Gandlevsky’s late experimentalism, the poems maintain a continuity of comic melancholy. Elegiac colors have always tinctured his poems, but as his poems reach past midlife into old age, his backward glance to his childhood and youth sometimes feel bathed in nostalgia:

Bright ochre and rust delight these old eyes.

Between roofs, a cloud grows out of itself.

Wind gathers, drags leaves by their scruff,

Batters a fountain, a mag of expired styles.

The blue autumn light. I dig it like no one.

There’s snow on the roof, but fire in the oven.

What I would give to wait at the train

For a stylish black-coated twentyish woman.

What is more traditional than a poet singing the praises of autumn, the yellows and reds seen by the poet as ochre and rust? That paradox, of the artist’s colors and of metal turning rusty, captures Gandlevsky’s mixing of memory and desire, of beauty and ugliness, of love and dying. This autumn is not only a season, of course, but the poet’s struggle against aging, against expiring. Despite his graying hair—”snow on the roof”—the poet’s desire flares up in his chest. (The Russian expression for an older person engaging in midlife crisis behavior is, literally translated, “gray hair on the head, demon in the rib”).

Yet Gandlevsky remains quicksilver and self-mocking, irreverent both with the poetic tradition and with himself. As one poem goes:

I said farewell to the Falstaff of youth

And took my seat on the train.

In the rocky process of evolution,

I turned from playboy to lone wolf.

And nonetheless April

With its non-alcoholic drops

Still pounded my head like schnapps.

Should I hang a house for birds,

Aim for some laudable goal?

Or should I just aim and fire?

Long story short, I will not be consoled.

No matter the particular life that you face, you will say farewell to the Falstaff of youth, but that doesn’t mean that he won’t go away without a fight.

When I first met Gandlevsky, in 1993, he’d already reached midlife, craving a steady, tidy existence with Lena, his wife, and his young children Sasha and Grisha. He’d recently begun editing the journal Foreign Literature, which he continues to this day. We met outside the metro stop. Charlie, his Boxer, panted next to him, his tongue outside of his mouth.

We wandered through the streets of Moscow. Gandlevsky stopped short, and pointed to the roof of a crumbling monastery. It was here, some years ago, he said, he once shared a bottle of vodka with a drinking buddy. Today, those days are gone. His kids are grown and he’s a grandfather now. He quit smoking, and prefers burning time in his garden.

Thirty years ago, I chose to translate Gandlevsky because I believed he captured the spirit of his age more scrupulously, more intensely, than any other poet of his generation. His friend, the poet Aleksey Tsvetkov agreed, saying, “With the exception perhaps of Pushkin, I do not know another example of a poet merging with his time to such an extent that that time could be—and probably will have to be, at least in part—reconstructed based on his poems.”

He will, of course, remain Russian until the end. Wherever he is, he will be writing into freedom.But I have gone back to his work, again and again, not simply for its documentary or historical value, nor for its youthful insouciance or its critical sentimentalism. Generations come and go, as do brands and bands and slang, but what remains is the haunting music of the heart’s longing, affixed by mere words to a page.

Poetry is not a commodity but a way of being, a way of inhabiting an interior homeland. In contrast to the professional productiveness and frenzied graphomania of some poets, Gandlevsky works slowly, writing only a handful of poems every year. He still spends weeks, even months, composing a single poem, turning it over in his mind as he goes about his day, taking walks and working with the earth. When, after a particularly extensive two-hour recitation of his poems, I’d asked him how he’d memorized all of it. “I don’t memorize them,” he said. “That’s how I write them.”

For quite some time, rumors circulated that Gandlevsky was going to emigrate from Russia and move to Israel. Given the political turn of the country—or perhaps, turning back—it’s no wonder. When, in 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, Gandlevsky decided to move to the Republic of Georgia, where he writes now, in exile. In addition to fears about his family’s safety, he also shared another reason. “I am seventy years old,” he wrote to me, “almost my whole life has been dominated by people with whom I want nothing to do. Can I at least live the last years of my life—I don’t know how many of them I have left—by myself, in a country that has aroused my strong sympathy since my early youth!?”

He will, of course, remain Russian until the end. Wherever he is, he will be writing into freedom. And when he passes, the poems will be the testament to that invisible labor. To write is to make a home amid our political or spiritual or actual exile. “My homeland,” he said back in 1992, quoting another Russian writer, “is Russian poetry.”

The gift of reading Gandlevsky in translation is to visit a vision, amid war and exile, of a homeland made of words.

______________________________

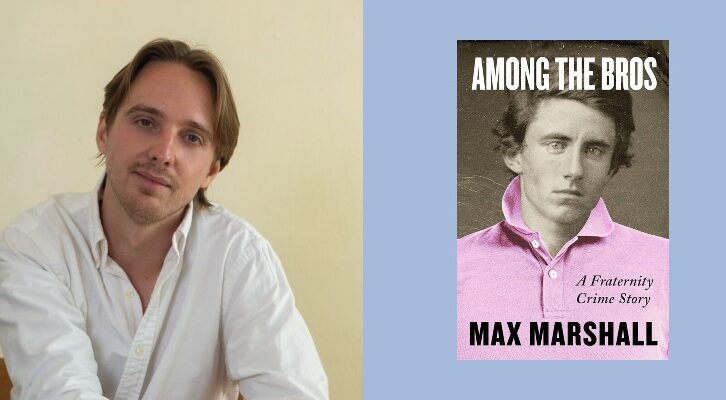

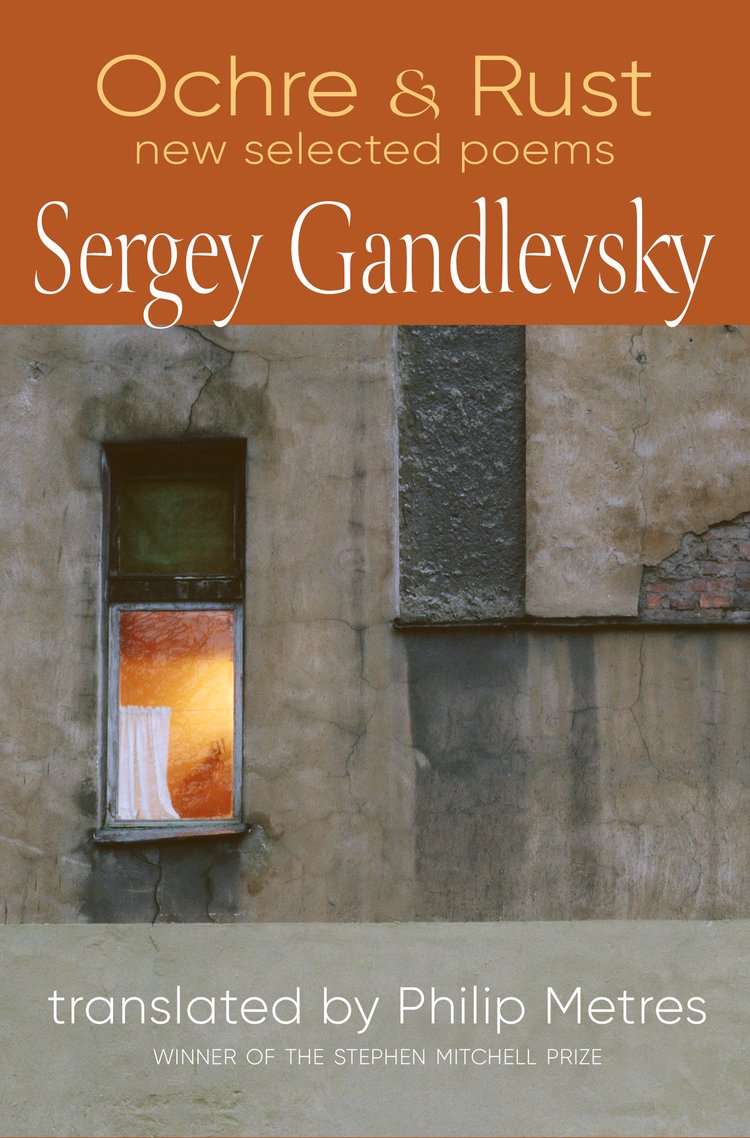

“A Homeland Made of Words” by Philip Metres, from the introduction to Ochre & Rust: New Selected Poems of Sergey Gandlevsky (Green Linden Press, 2023).