A Master Class in Words: On the Vitality and Vividness of The Iliad‘s Opening Lines

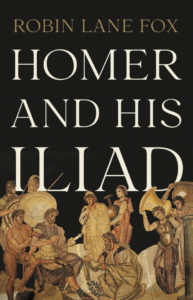

Robin Lane Fox Considers the Movement of Homer's Epic

The first verses of the Iliad cleverly set up what will follow. Achilles’ wrath laid “countless pains on the Achaeans”: suffering and tragedy, we realize, will be prominent in what is to come. The wrath “sent many mighty heroes on down to Hades,” god of the underworld, and “made them prey for dogs and all the birds.” A death without burial was dreadful for a Greek, especially if birds and animals devoured the corpse: the wrath, then, had consequences of extreme horror. “And the plan of Zeus was being fulfilled”: importantly, Homer uses the imperfect tense here, meaning “was being/continued to be.” For the moment Zeus’ plan is left undefined. It will unfold with the action, but it is already linked to countless sufferings.

This marvelous beginning is rich in implications for what will follow in the poem. It gives a sense of the art and intricacy with which Homer composed. Details like Briseis departing unwillingly or Thetis alluding only in general terms to her past favors were not the work of a poet who was being guided in a traditional direction by nothing but traditional phrases. Nonetheless, he presents individuals and items with recurring phrases or adjectives, “swift-footed Achilles,” “white-armed Hera” or the “wine-dark sea.” This blend of recurrent phrasing and individual art will be a valuable clue to his method of composition.

Important points about the poet and his listeners follow from it. Evidently, Homer knew he was addressing people who were familiar with general tales of Troy and their heroes: he introduces Agamemnon by calling him only the “son of Atreus” and refers to Achilles’ beloved Patroclus only as the “son of Menoitios” when he is first mentioned. His narrative never even mentions Troy or the Trojans, taking them for granted. They are mentioned, rather, in speeches. No less than 60 percent of this first book is presented as direct speech, a remarkably high proportion. Chryses the priest, five of the Greek heroes and five of the divinities speak, but Chryseis and Briseis remain silent, not because Homer belittles women but because they are enslaved girls and have no agency in what happens.

The clear line of the action would be delayed if they spoke while unable to influence it. Three goddesses, by contrast, deliver speeches, because their words can, and do, shape the plot.

Why does this opening have such vitality and beautifully controlled vividness? Major reasons are the even flow of its meter and poetic language, aspects which require a good knowledge of Homeric Greek. Others are accessible even in translation. One is that emotion runs high in many of the speakers, as the narrative states, emphasizing their fear or anger, distress or wrath. Weeping too is explicitly presented. It is not a shameful or unmanly response: when Achilles loses lovely Briseis, he does not lose heroic status when he sits by the wine-dark sea and sheds tears.

Another reason is that speeches implicitly reveal their speakers’ character, whether the haughty inconsiderateness of Agamemnon, causing the sending of a plague and then the quarrel, or Achilles’ swift temper, becoming violently enraged, or Nestor, dwelling on his past with the habitual discursiveness of an old man. Speakers also characterize one another, using the word “always” to enlarge our sense of them beyond the moment. Strife and battles, Agamemnon says, are “always” dear to Achilles. Hera, Zeus says, is “always” thinking what he is planning secretly and Zeus, Hera says, is “always” glad to make secret decisions apart from her. We know more of them as a result.

In this first book there are no long similes, though they are hallmarks of the next book and beyond. There is, however, a brilliant use of words in action. Homer narrates events in the past tense, but makes his speakers give speeches in the present, a variation which brings the speeches to life and makes the poem’s world, though far in the past, immediate for his listeners. Speaking in the present, his speakers allude to the past, “if ever,” and to the future, “some day,” widening the scope of the poem’s timescale.

To an extent which has not been recognized, the first book of the Iliad teems with instances of how to do things with words.Words, when spoken, announce what will come to pass, as a neat exchange between Achilles and his mother Thetis shows. “I will speak out,” Achilles tells her, “and I think this will be fulfilled,” that Agamemnon “may soon lose his life through his insolences.” In reply Athena tells him, “So I will speak out and it will be fulfilled for sure,” that one day he will receive three times as many glorious gifts because of this insolence. She does not enact the future by what she says here: as a goddess she predicts it with emphatic certainty. Unlike Achilles, she does not “think”: she knows, and so Achilles promptly speaks to Agamemnon in accordance with what she has said. “Insult him with words,” Athena has told him, “as to what will come to fulfillment,” and so he insults Agamemnon with renewed vigor, using compound adjectives which never recur in the poem. Knowing what will happen, he also issues threats, stating what he will do.

Simply by being spoken, words bring threats and insults into being. Words also enact oaths: they are sworn by being uttered, nothing else. Achilles takes up a scepter, studded with gold nails, and swears by it, adding solemnity to his oath, but what makes his oath exist are the words he speaks. The same is true of hymns and prayers. By being uttered, words from elderly Chryses constitute prayers, just as words from the Greek delegates or from the Muses constitute hymns by being sung. Words also engender promises, like Zeus’ words to Thetis when he tells her that she must go away but “these things will be my care, how I shall bring them about.” He then says he will nod with his head, the greatest sign, and that “my [word] is not revocable, deceitful nor unfulfilled, whatever I nod to with my head.” His words constitute a promise, which is confirmed by his movement.

To an extent which has not been recognized, the first book of the Iliad teems with instances of how to do things with words. The subject is much studied by modern philosophers, but they have not turned to the Iliad for examples. In its beginning Homer deploys a wide range of what they call speech-acts, making it exceptionally vivid and fast moving. He also attends to how words are received, specifying their effects on their recipients. What is done with words adds force to its opposite: silence. Old Chryses is silent, walking by the sea, and so too are the heralds when they come unwillingly to reclaim Briseis from Achilles. The supreme silence is Zeus’, as he thinks through the implications of Thetis’ request.

Significant speech and significant silence are not the only contrast which this book deploys. Throughout, it has brilliant variations of pace. Homer uses brief speeches to help him present the back-story which leads to the quarrel. The speeches that express it then increase in length and strike off one another as they escalate. Old Nestor then slows the pace with fifteen verses in which he recalls “better men than you,” past heroes who fought the centaurs, with whom “mortal men now on earth would never fight.” His speech aims to settle the quarrel, but fails, whereupon a flurry of angry words resumes and the story regains pace.

Speeches are preceded by movement, as each speaker takes up a place and only then begins to speak. The entire book is alive with it, yet the actions that accompany it proceed at times in a prolonged sequence. Agamemnon launches a ship; he chooses twenty rowers; he puts animals on board to be sacrificed to Apollo; he brings faircheeked Chryseis and sets her on board too; many-wiled Odysseus embarks as leader. They “sail over the watery ways,” while Agamemnon orders the Greeks back in the camp to purify themselves; they throw the washed-off filth into the sea; they sacrifice many bulls and goats on the shore to Apollo: “the savour went up to heaven coiling in the smoke.” In only ten verses Homer narrates so much on two fronts, but never with breathless haste. The meter of his verse moves smoothly and swiftly, helped by the adjectives which repeatedly attach to particular nouns and persons, “fair-cheeked Briseis,” “resourceful Odysseus,” “watery ways,” “the unharvested sea.” As so often, it is worth visualizing the range of what he presents, even if listeners could not pause and dwell on it in that way. In the time taken to recite these ten verses, not even a film could show so much in a sequence of shots. Homer’s words convey more, more swiftly, than pictures.

_____________________________________________________

Excerpted from Homer and His Iliad by Robin Lane Fox. Copyright © 2023. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.