“A monster can look like whatever it wants”: On the Allure of Literary Monsters

Adrian Van Young on the Monstrous Stories That Shaped Him

The monster must be ten feet tall.

Its musculature heaves and gleams, as though flayed. Its unblinking eyes stand out spider-egg white. Its head is roughly pumpkin-shaped because that’s where the monster gets its name, though the head really looks like some sort of batard, channels of mold running through it like veins. It has strange armature on its shoulders and back that at one point in time might’ve fluttered with wings. It moves all herky-jerky, its tail and claws snapping, this ambient rattling hiss coming off it.

Nobody can stop it. Nobody would dare.

For me, before Mary Shelley’s sorrowful creature or H.P. Lovecraft’s cephalopod or Toni Morrison’s pregnant vampire ghost, there was Pumpkinhead. Released in 1988, starring Lance Henrikson of Aliens and Near Dark-fame, and marking the directorial debut of creature effects makeup master, Stan Winston, Pumpkinhead is deeply stupid. Like as not, you haven’t seen it. Though maybe, if you’re near my age, you’ve seen the VHS-display box: the monster in question among twisted tree roots, framed against a harvest moon.

Reader, I rented this film and I watched it, I wish I could say less than dozens of times. And always, with zeal, I rewound to the scene where Lance Henriksen conjures the titular demon—its bizarro flesh hardware, its loaf of a head.

In truth, I’d always been that kid, the one who’s just a little creepy. In kindergarten, I usually spent my free time in class hunched over scotch tape, scissors and construction paper, Frankenstein-ing together corpse-kings and chimeras. In second grade, I “published” my first monster story, a book about a werewolf (whose title could’ve doubled for a book about a gigolo): “Night Man”; my teacher at Beth Israel Day School, Ms. Cohen, bound the pages and spine with super-glue and made a laminated dust-jacket with a werewolf drawing on it.

When I was recovering from a tonsillectomy at eight-years-old, my father showed up at my hospital bedside with a get-better gift, a hard-plastic rendition of Star Wars’ “Rancor Monster,” who Luke Skywalker kills underneath Jabba’s palace. The Rancor is enormous with T-Rex like claws, its maw bristling with crooked teeth.

Some part of me must’ve always sensed this. Monsters are beautiful—this was my truth.“Beauty, in some ways, is boring,” writes Umberto Eco in his book-length treatise on the grotesque in art, On Ugliness. “Beauty is finite, ugliness is infinite like God.”

Some part of me must’ve always sensed this. Monsters are beautiful—this was my truth.

When H.P. Lovecraft in “The Call of Cthulhu” describes how a ship of monster-hunters “[drives] on relentlessly” toward a creature of a “vaguely anthropoid outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind” rising out of the waves before it, and the creature subsequently splits before the ship’s prow, only to “[recombine] in its hateful original form,” I longed to be flicked at by that “mass of feelers,” feel the breeze from those “long, narrow wings” on my cheek.

Or when Clive Barker, in his novella The Hellbound Heart (popularly adapted into the 1987 film Hellraiser), describes the arrival of BDSM interdimensional entities, “The Cenobites,” one of whom “[teases]” “by the motion” of its speech a series of “hooks that transfixed the flaps of its eyes and were wed, by an intricate system of chains passed through flesh and bone alike, to similar hooks through the lower lip…exposing the glistening meat beneath,” I swore I could hear the light clash of those chains, my dread blossoming at that mention of “meat.”

Like the child rewinding Pumpkinhead, I returned to these monsters, again and again. I marveled at the details of their strange physiognomy. I savored the jolt of their sudden appearance. Purely based in how they looked, they awakened within me a species of wide-eyed, magisterial terror close to that which Edmund Burke identifies in his 1756 essay “A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful.” But it wasn’t until I read Toni Morrison’s Beloved that I truly gasped what a monster could do.

Morrison’s novel, in case you’ve never read it, is a harrowing and visionary postbellum Gothic fable of American slavery that centers upon formerly enslaved woman, Sethe, who attempts to construct something resembling a stable life for herself and her loved ones even amidst the recurrent trauma of slavery and its aftermath. (The novel draws inspiration from the historical figure Margaret Garner, who, after escaping slavery in 1856 only to be recaptured under the Fugitive Slave Act, killed her own two-year-old daughter with a butcher’s knife rather than see her re-enslaved.)

As the novel progresses, the titular character “Beloved” (an ominous pet name for the ghost of the murdered child who haunts Sethe’s house) becomes a preverbal, living repository for the collective trauma and viciousness of America’s “Original Sin”—part hungry ghost, part vampire, part bad seed. At the end of the novel, as “thirty neighborhood women” gather in Sethe’s yard to catch sight of Beloved, Sethe and the living ghost of her murdered daughter clasp hands and come out.

“The devil-child was clever,” Morrison writes. “And beautiful. It had taken the shape of a pregnant woman, naked and smiling in the heat of the afternoon sun. Thunder-black and glistening, she stood on long straight legs, her belly big and tight. Vines of hair twisted all over her head. Jesus. Her smile was dazzling.”

A change of pace from Pumpkinhead, but also not so far away. Morrison cued me into something I had never once considered as a monster-connoisseur: a monster can be—should be—more than a monster. And a monster can look like whatever it wants.

In Gustav Meyrink’s The Golem (1915), the monster is more than a life-endowed clay titan; it’s an ensign of Jewish suffering and persecution, spending its rage on the city of Prague. In Mariana Enriquez’s stories of post-Dirty War Argentina (Things We Lost in the Fire, 2016) you might think the real monsters are Chthonic slum deities or rabid black hellhounds patrolling a quarry, but they’re also the scars of political terror, the shadows of Los Generales.

The monsters in Angela Carter’s stories (The Bloody Chamber, 1979), who wear the faces of multiple-murdering marquises, humanoid tigers, and ancient vampire queens, turn out to be stand-ins for cultural misogyny, erotic trespass, and anxiety surrounding unbridled female sexuality. While in Carmen Maria Machado’s story “Especially Heinous: 272 Views of Law & Order SVU” (Her Body and Other Parties, 2017), the ghost “girls-with-bells-for-eyes” are pure nightmare fuel, but also a potent metaphor for the fetishization of sexual violence.

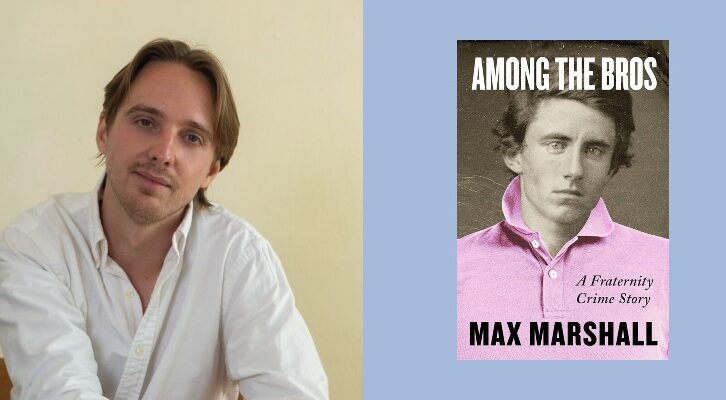

All this darkling wisdom I’ve taken to heart. My new collection, Midnight Self, is a taxonomy of the monstrous and strange in which I’ve done my very best to make my creatures more than fetching. It boasts a sleep-deprived mother’s Babadook-esque dopplegänger, an ancestral house that subsists on male virgins, and a twisty tube-man that eats transphobic bullies. It has Civil War zombies that march on the living, and a haunted gnome doll that preserves an old woman.

All of these stories began with a monster before deepening what a monster can mean. From their high thrones in the Monstrosphere, I hope Morrison and Carter are looking on proudly.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I sketched a lot with my then seven-year-old son, somewhat of a monster-nerd himself. One day, I decided to draw him a rendition of something from my fiction, a hideous alien creature called “The Skin Thing” from a story of the same name who preys ritualistically on a group of exhausted space colonists.

In the story itself, “The Skin Thing” is described as a twenty-foot-tall abomination with an eyeless, horse-shaped head, a puppet mouth, and a tapering worm-body that it drags across the desert wastes of the colonists’ planet by way of two tentpole-like appendages connected on either side of the creature’s hackles by a “tensile wall of thick pink skin.” “The Skin Thing” is more than the sum of its parts; by the end of the story it comes to represent, among other things, the dangers of groupthink, the painful indifference of the natural world, the brutality of human tribalism. Also—who am I kidding— a just a super dope monster.

As I finished drawing, my kid asked, “What is it?”

At the time I was distracted, still absorbed by my creature. I was trying to get the head just right, the sharp ends of the tentpole arms. I squinted at “The Skin Thing’s” outline. “I guess it could be lots of things.”

______________________________

Midnight Self by Adrian Van Young is available via Black Lawrence Press.