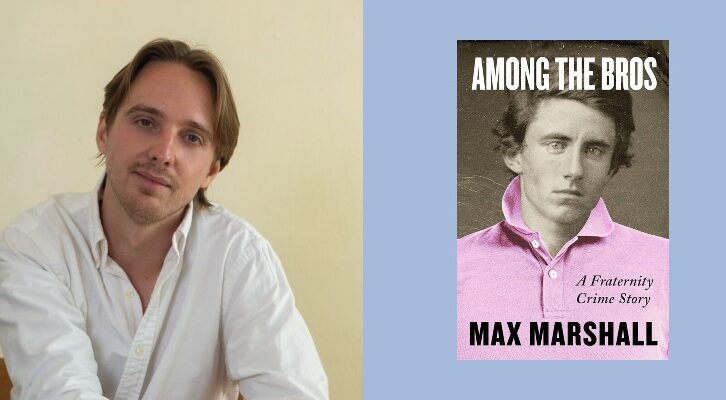

Jasmin Iolani Hakes on the Many Languages of Hawai’i (Including Hula)

In Conversation with Brad Listi on Otherppl

Jasmin Iolani Hakes is the guest. Her debut novel, Hula, is out now from HarperVia.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

From the episode:

Brad Listi: There’s a ceremonial aspect to hula. And also it’s obviously movement, it’s dance. It’s also narrative. This is a storytelling medium. This is a way for Hawaiians to pass down stories about who they are and what they believe, and stories about Hawaiian cosmology. Right?

Jasmin Iolani Hakes: I mean, think about Greeks and Romans. It was epic poetry. That’s how you captured history. That’s before we could write these things down—that’s how they lived, was you tell the story. And so, these stories and these hulas, that’s why they talk about gods and goddesses and myths and legends, but they also talk about volcanic events and the mist and how that came to be, and why this ocean does this, and what these fish do. It’s knowledge.

Brad Listi: I found it poignant to be reading a novel about a culture that’s kind of fighting to survive, and to be reminded of the critical importance of narrative and storytelling to the survival of any group of people or culture. If you can’t tell these stories, if nobody knows these stories, and if nobody knows this language…

Jasmin Iolani Hakes: I grew up in such an interesting time, the 80s and 90s. I had one cousin—when I say cousin, friend-cousin, it’s all the families that are intermeshed—there was only one that when he had to call home to his mom, he would speak ʻŌlelo; he would speak Hawaiian. And everybody would hush to just listen to him because no one spoke Hawaiian, not fluently. You had pidgin, which is I guess my first language.

Brad Listi: And what do you mean by pidgin?

Jasmin Iolani Hakes: It’s kind of the linguistic mixed plate. It’s the Portuguese and the Filipino and the Japanese and the Chinese and all of these. It’s a Creole, it’s a dialect. And every island has a slightly nuanced difference. So if you’re a local, you can kind of tell, that guy’s from Maui, that guy is from Honolulu. They’re nuanced. But it very much is its own language. It has its own inflections and meanings. And so it was interesting to write it in pidgin, and I did that very deliberately.

Pidgin was something that you were very shamed if you spoke it to a certain extent. There’s still a lot of discrimination. You’re assumed to be illiterate or not educated. Unrefined. My mom was very shamed. Generations before her were very shamed for not speaking English-English. And so my mom was very strict about no pidgin in the house. It was a constant battle. Because she felt like it was going to be a handicap, a disadvantage.

There has been a renaissance that I’ve tried to highlight the coming of and the evolution of in Hula. But going back to being ʻŌlelo, that all started in the 70s, 80s, and 90s. That cultural revolution and renaissance was very much tied to the language itself, because you had to have a group of people come together and say, We’re going to create a curriculum on paper. It can’t just be passed down through songs and hulas. We’re going to create a curriculum on paper that actually teaches our youth the language.

And Hilo was one of the first places that had a charter school that was only taught in Hawaiian, only ʻŌlelo. It was a revolutionary thing because you had this very static language that had been kept alive only underground, so to speak, and so it had to be artificially fast forwarded, because there were no words for car and computer and internet and things like that. I can’t imagine the undertaking.

It was just kind of happening in my backyard, and now when I fly back, like a trip or two ago, there were two airline stewards and they were speaking to each other very casually in ʻŌlelo. It’s amazing to me how quick—just a couple of generations. Now all of my nieces and nephews are so far ahead of anything that me or my cousins or my generation had access to or an awareness. Because from language, now it’s cultural ways, and now part of their curriculum is being outside and being a part of Hawai’i, not just as a homogenous people, but as almost subjects of the kingdom. Multiple ethnicities coming together to perpetuate the ways of this kingdom, or these people, or this land.

*

Jasmin Iolani Hakes was born and raised in Hilo, Hawai’i. Her essays have appeared in the Los Angeles Times and the Sacramento Bee. She is the recipient of the Best Fiction award from the Southern California Writers Conference, a Squaw Valley LoJo Foundation Scholarship, a Writing by Writers Emerging Voices fellowship, and a Hedgebrook residency. Dance has always been central to Jasmin’s life and creativity. She took her first hula class when she was four years old and danced for the esteemed Halau o Kekuhi and the Tahitian troupe Hei Tiare. She worked throughout college as a professional luau dancer. She lives in California.